Since it’s inauguration week, we’re looking at a few of the most important ones in national history.

We tend to see presidential inaugurations as staid events with a familiar refrain and symbolism. It wasn’t always that way — no one had any idea George Washington was going to give a speech after his 1789 inauguration as the nation’s first president — but the passing centuries have given the event a common ceremony and narrative arc.

Most inauguration speeches, like most all speeches, are not long remembered. But some are burned into the national memory, like Washington’s phrase, “the sacred fire of liberty,” from his unexpected speech.

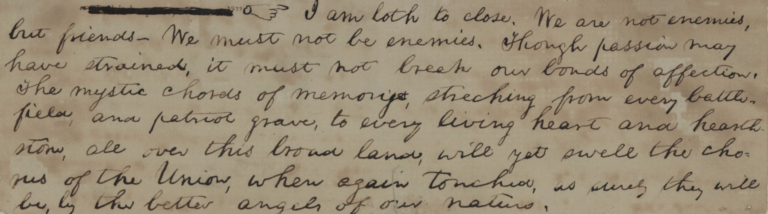

Both of Abraham Lincoln’s inaugurations were memorable, in part because of his eloquence but in larger part because of the Civil War that was unfolding at his first inauguration and ending during his second. Both speeches featured phrases that are still quoted. In the first, there was “the mystic chords of memory,” and, no doubt the most famous, “the better of angels of our nature,” scrawled in at the very bottom of the last page.

As Michelle Krowl, the Library’s Civil War and Reconstruction expert, details in the video above, Lincoln took his second inaugural oath on March 4, 1865. The war was all but done. Robert E. Lee, the Confederate general, would surrender just a few weeks later on April 9. Lincoln would be assassinated six days later, on April 15.

This second speech, given after a morning of wet, miserable weather, took place on the East Portico of the Capitol. It was the first inauguration after the Capitol dome was completed, and it was the first at which African Americans — some wearing their Union army uniforms — were allowed to attend.

Lincoln’s vice president, Andrew Johnson, a former senator from Tennessee, took his oath of office in the Senate chamber around noon. The gathering then moved outside for Lincoln’s oath and address. The weather, so awful for most of the day, had calmed. Just before he began speaking, the sun came out, casting the day in a new light.

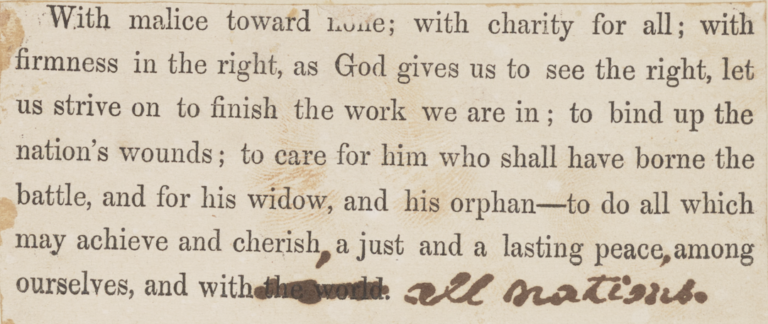

The typeset speech — Lincoln cut and pasted paragraphs onto the page — ran just 700 words and fit on a two-columned page. He stood behind a small metal table, put on his glasses and read. It could not have taken more than a few minutes.

Lincoln began with a recounting of the situation of his previous inauguration. He noted that “insurgent agents” had been in the city then, intent on tearing the nation apart. He soon got to the point of what the war had ultimately been about — slavery. Though he said that the government had not originally sought to abolish slavery before the war, just to limit its territorial expansion, it was now committed to destroying it:

“Yet, if God wills that it continue, until all the wealth piled by the bond-man’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash, shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said “the judgments of the Lord, are true and righteous altogether.”

Then, in his concluding lines, he turns to the future with hope. It was a vision of reconciliation, of renewed peace and of a nation united once more. The monumental phrase is “With malice toward none; with charity for all.” It was the perfect summation for a president trying to bring a fractured republic, then in the last throes of the war, back together.